By Daniela Döring and Johanna Lessing

The challenges of the current pandemic are sometimes balanced by small rays of hope. In 2020, many years of preparation culminated in the opening of the Ghent University Museum (GUM) to the public, with short visits possible via advance online booking. The museum’s Forum for Science, Doubt and Art represents a new kind of exhibition program, in which academic objects aren’t presented as the results and conclusions of scientific work; rather, according to the museum’s website, the subject of the exhibition is the brain of the scientist itself. We can watch academics thinking and experience the rarely straightforward process, the errors and doubts, but also the beauty, of scientific work.

Due to the pandemic, we haven’t yet been able to visit the exhibition ourselves. However, shortly after the opening of the museum, a small but spirited accompanying booklet titled “The Museum of Doubt. A Modest Manifesto by a Science Curator” was published by GUM Director Mirjan Doom. A TED talk by the museum curator and an interview with Sébastien Soubiran (President of Universeum, European Academic Heritage Network) also provide exciting insights into the curatorial endeavour. For us, this is enticement enough to take a closer look at the book’s emphatic plea.

It’s not the outcome that matters, it’s the process

The unwavering story of great scientific achievement and its masterful (usually male) inventors and discoverers leads to a particular similarity between science museums. Marjan Doom refers to them as “carbon copies of the same thing over and over again” (p. 37), and immediately sets out to remedy this monotony. Her book “The Museum of Doubt: A Modest Manifesto by a Science Curator” is both a curatorial creed and a call to make science education less authorial, less restrained and less secure. Doom argues the benefits of presenting to the public a more human – by which she also means more flawed, erring and vulnerable – picture of science; for the reduction of science to its results ignores why and how researchers proceeded, the myriad detours and setbacks they faced. The presentation of scientific work as the success of one (highly impressive) individual misses the fact that such achievements are usually only possible due to the efforts of entire research teams and the contributions of various disciplines.

Science doesn’t proceed in a straight line. Instead, the exploratory path of the research process is characterised by ever new types of scrutiny, new experimentation and reorientation. According to Doom’s central premise, doubt is much more crucial for scientific work than is the verified result ready for publication. It drives thought processes and optimises experimental designs. It forms the actual core of creative, scientific work. Doom believes that in presenting science’s doubts and winding pathways, museums not only have the potential to facilitate a more appropriate and accurate discussion of its practice; rather, transparent and participatory insight into the methods of dynamic research represents the political responsibility of science education to stand up against dogmatisation, and at the same time to advocate for democratic and, in the context of error culture, human cooperation. At the GUM, doubt is therefore the driving force behind the curatorial approach.

New – or old – alliances?

But if the production of academic knowledge is to be presented as an unfinished, experimental process, how exactly should this be achieved in the exhibition space? “The solution is not to practice science in an ivory tower without participating and then talk about the success stories” (p. 15), states Marjan Doom. The author strategically uses the alliance between art and science to realise this aspiration, so that art becomes a spotlight for other narratives, for new questions and surprising perspectives, for unexpected constellations of objects, for emotional impact and intellectual involvement. Art is recognised as possessing the capacity to evoke independent critical thinking “outside-the-box” (p. 21), preventing the blind acceptance of truths and activating social responsibility. As a mode of knowledge, Doom sees art as being diametrically opposed to quantified and objectified (scientific) knowledge. Art and doubt become curatorial strategies that (are intended to) serve as refractive lenses for the linearity of conventional academic exhibitions.

Surprising connections

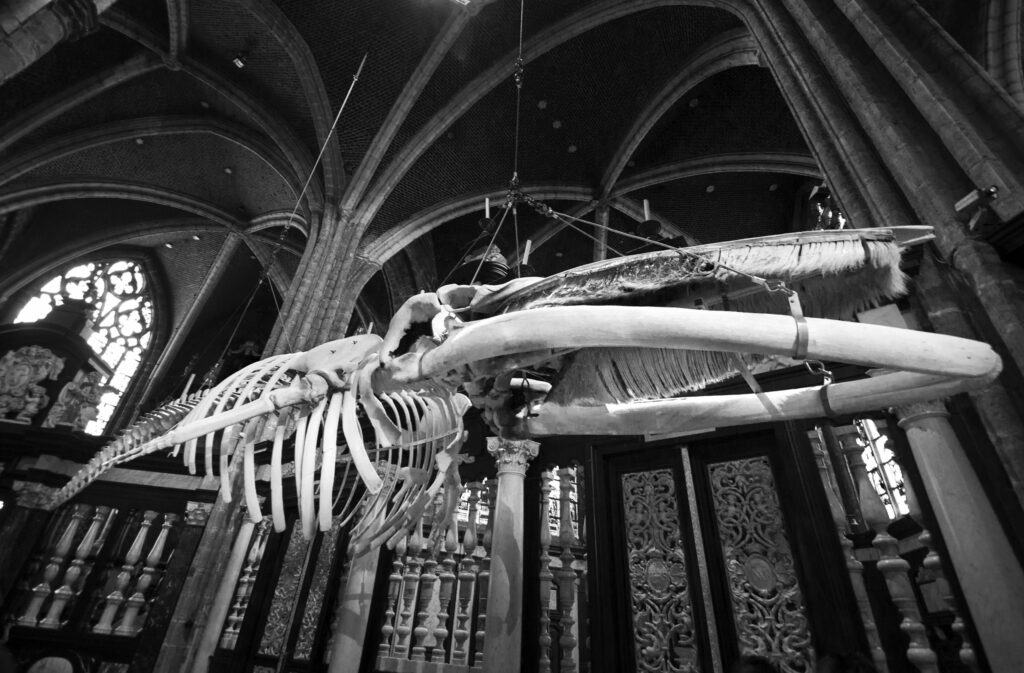

Okay, but doesn’t art as a counterpart to science fall short? What exactly can it achieve? According to the curator, art can help us move beyond the supposed linearity of science because it is associative and raises existential questions. She believes that the shared experience of viewing a (scientific) exhibit can have comparable effects, and that the alliance of art and science makes this possible, or at least facilitates it considerably. The important thing is to surprise visitors to the museum with a novel narrative. To explain how this works, Doom uses the example of the exhibition “PostMortem”, which she curated together with Chantal and Pascal Polier in 2015 (p. 33f.). It was held in the then recently vacated Institute for Forensic Medicine, and its corridors, offices and dissection rooms became exhibition spaces as well. The recent history of the dissecting table was presented to the public using video installations, and through artistic re-enactment an immaterial knowledge becomes visible between space, instrument, visitors and artwork. Another exhibition that exemplifies the spirit of the GUM is the installation of a giant whale skeleton in 2017 in Saint Bavo Cathedral in Ghent. In lieu of an object description, the skeleton was accompanied by a poem by Peter Verhelst. It is precisely this kind of presentation that challenges visitors to create (their own) connections between the two.

In this way, spaces of imagination that are personal, new and unpredictable can arise, and it is precisely this individual dimension that is so exciting for Marjan Doom. The element of surprise is achieved by presentations that consciously include the surrounding space and subvert individuals’ expectations of science exhibits, whose effects go beyond the pure conveyance of information content. The spatial constellation ‘stores’ its information in “deeper layers, as is the information content connected to it” (p. 31 f.). The curator is aware that this can be challenging. It is indeed her aim to take visitors out of their comfort zone and to plant “a bit of healthy stimulating confusion” in their minds (p. 33).

A universal language?

Alright, but who is the imagined audience? Which expectations and conventions are meant to be defied? And what is the curator’s relationship to them? In the Museum of Doubt, art is understood as a non-scientific and overarching language. It facilitates the translation, so to speak, of special, discipline-specific languages into another, quasi-universal language. According to Marjan Doom, such a personal and unique experience is much more difficult to achieve with scientific instruments than it is with art – the latter touches on universal and timeless things that unite us as human beings and make a shared experience possible. And yet, this universal language is not as universally comprehensible and accessible as it seems. Rather, it assumes prior knowledge of science exhibitions and a familiarity with art. What remains curiously unaddressed here is the objectivity or truth claim of the research itself. While the exhibition, or in a broader sense the display and presentation of scientific work in and for the public, is meant to expand and multiply individual spaces of experience, the facts, the results and apparatus, remain untouched. One could say that the myth of science as a linear success story is being transformed into an aestheticization of research. While the content has changed, the logic of science communication, understood as transmission of information from A to B or from expert to layperson, has not.

Curating with Marjan Doom means pursuing a new artistic narrative in which surprises as well as error and vulnerability are suspended in the paradigm of doubt. But it also entails following a new master narrative, namely that of the “science curator”, which in the course of her account Doom reveals herself to be; a narrative that continues to present people with hard facts of research in new (correct) ways. But what if art and science, as well as exhibition and research, were not so rigidly separated? And what if both art and exhibitions were not used to illustrate science in such a subordinate and instrumental way? Couldn’t the critical, self reflective and personal element be found in science itself? And could the exhibition space itself then become a place of research? These questions are very much at home in the Museum of Doubt, where we can look forward to further surprises.

Publication by Marjan Doom: The Museum of Doubt. A Modest Manifesto by a Science Curator. Academia Press 2020

Daniela Döring is a postdoctoral researcher at the “Exhibiting Knowledge | Knowledge in Exhibitions” Doctoral Research Group. She investigates contemporary exhibitions of academic collections and scientific practices.

Johanna Lessing is a PhD student at the “Exhibiting Knowledge | Knowledge in Exhibitions” Doctoral Research Group and is researching the exhibitability of human remains in scientific collections.

This article was editorially supervised by Sonja E. Nökel, student assistant at the “Exhibiting Knowledge | Knowledge in Exhibitions” and translated by Michael Labate.

Leave a Reply